How Much Money Does Medicare Collect Each Year

Medicare, the federal wellness insurance plan for more than than lx one thousand thousand people ages 65 and over and younger people with long-term disabilities, helps to pay for hospital and physician visits, prescription drugs, and other acute and post-acute care services. This issue brief includes the nearly recent historical and projected Medicare spending data published in the 2019 annual written report of the Boards of Medicare Trustees from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary (OACT) and the 2019 Medicare baseline and projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

| Cardinal Facts |

|

Overview of Medicare Spending

Medicare plays a major office in the health intendance system, bookkeeping for twenty percent of full national health spending in 2017, 30 percent of spending on retail sales of prescription drugs, 25 percent of spending on hospital care, and 23 percentage of spending on doctor services. In 2018, Medicare spending (net of income from premiums and other offsetting receipts) totaled $605 billion, bookkeeping for 15 percent of the federal budget (Effigy 1).

Figure one: Medicare every bit a Share of the Federal Budget, 2018

Historical Trends in Medicare Spending

Trends in Medicare Do good Payments

In 2018, Medicare benefit payments totaled $731 billion, up from $462 billion in 2008 (Effigy 2) (these amounts do not net out premiums and other offsetting receipts). While benefit payments for each part of Medicare (A, B, and D) increased in dollar terms over these years, the share of total benefit payments represented by each part changed. Spending on Part A benefits (mainly hospital inpatient services) decreased from 50 percent to 41 pct, spending on Part B benefits (mainly md services and infirmary outpatient services) increased from 39 percent to 46 percent, and spending on Part D prescription drug benefits increased from eleven percent to 13 pct.

Effigy 2: Medicare Do good Payments for Part A, B, and D, 2008 and 2018

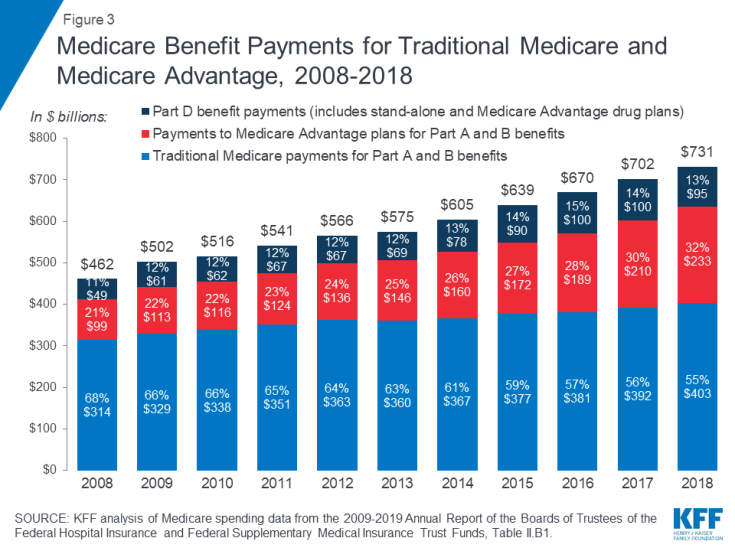

Another notable change in Medicare spending in the past x years is the increase in payments to Medicare Advantage plans, which are private wellness plans that embrace all Part A and Part B benefits, and typically also Function D benefits. As a percent of full Medicare do good spending, payments for Function A and Part B benefits covered past Medicare Reward plans increased by nearly 50 percent between 2008 and 2018, from 21 percent ($99 billion) to 32 pct ($232 billion), as private programme enrollment grew steadily over these years (Figure iii). In 2018, 34 percentage of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, up from 22 percent in 2008.

Figure iii: Medicare Benefit Payments for Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, 2008-2018

The overall cost of administering benefits for traditional Medicare is relatively depression. In 2018, administrative expenses for traditional Medicare (plus CMS administration and oversight of Office D) were ane.3 per centum of total programme spending; this includes expenses for the contractors that procedure claims submitted by beneficiaries in traditional Medicare and their providers. This estimate does not include insurers' costs of administering private Medicare Advantage and Part D drug plans, which are considerably higher. Medicare'south actuaries guess that insurers' administrative expenses and profits for Part D plans were 10.7 percent of full plan benefit payments in 2018. The actuaries have not provided a comparable approximate for Medicare Advantage plans; however, according to a recent assay, uncomplicated loss ratios (medical expenses equally a share of total premiums collected) averaged 86 percent for Medicare Advantage plans in 2018, which means that administrative expenses, including profits, were 14 percentage for Medicare Advantage plans.

Trends in Total and Per Capita Medicare Spending

At that place has been a notable reduction in the growth of Medicare spending in contempo years, compared to prior decades, both overall and per beneficiary.

- Average annual growth in total Medicare spending was 4.four per centum betwixt 2010 and 2018, down from nine.0 percent between 2000 and 2010, despite faster growth in enrollment since 2011 when the baby blast generation started becoming eligible for Medicare (Figure 4).

- Average annual growth in Medicare spending per beneficiary was just 1.7 percent betwixt 2010 and 2018, down from 7.3 percent betwixt 2000 and 2010.

- Spending on each of the three parts of Medicare (A, B, and D) has grown more than slowly in recent years than in previous decades (Figure 5). For instance, the average annual growth rate between 2010 and 2018 was 0.ane pct for Role A, compared to iv.4 percentage in the 2000s, and 3.1 percent for Part B, compared to seven.0 per centum in the 2000s.

Figure 4: Actual and Projected Average Annual Growth Rates in Medicare and Private Health Insurance Spending, 1990-2028

Figure five: Actual and Projected Average Annual Growth in Medicare Casher Costs for Role A, Function B, and Part D, 1990-2028

Slower growth in Medicare spending in contempo years can be attributed in part to policy changes adopted equally office of the Affordable Care Deed (ACA) and the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). The ACA included reductions in Medicare payments to plans and providers, increased revenues, and introduced delivery system reforms that aimed to amend efficiency and quality of patient care and reduce costs, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), medical homes, bundled payments, and value-based purchasing initiatives. The BCA lowered Medicare spending through sequestration that reduced payments to providers and plans past 2 percentage offset in 2013.

In addition, although Medicare enrollment has been growing between 2 percent and 3 percent annually for several years with the aging of the baby nail generation, the influx of younger, healthier beneficiaries has contributed to lower per capita spending and a slower rate of growth in overall program spending.

Spending Trends for Medicare Compared to Private Health Insurance

Prior to 2010, per enrollee spending growth rates were comparable for Medicare and individual health insurance. With the contempo slowdown in the growth of Medicare spending and the recent expansion of private health insurance through the ACA, however, the deviation in growth rates between Medicare and private health insurance spending per enrollee has widened.

- In the 1990s and 2000s, Medicare spending per enrollee grew at an boilerplate annual rate of 5.viii per centum and 7.three percent, respectively, compared to five.ix percentage and seven.2 pct for private insurance spending per enrollee (Figure 4).

- Betwixt 2010 and 2018, Medicare per capita spending grew considerably more slowly than private insurance spending, increasing at an average annual rate of just 1.7 percentage over this time menses, while average annual individual health insurance spending per capita grew at 3.8 percent.

Medicare Spending Projections

Curt-Term Spending Projections for the Next 10 Years

While Medicare spending is expected to continue to grow more slowly in the future compared to long-term historical trends, Medicare's actuaries projection that future spending growth will increment at a faster rate than in recent years, in part due to growing enrollment in Medicare related to the crumbling of the population, increased employ of services and intensity of care, and rising health care prices.

Looking ahead, CBO projects Medicare spending will double over the side by side ten years, measured both in total and net of income from premiums and other offsetting receipts. CBO projects net Medicare spending to increase from $630 billion in 2019 to $ane.3 trillion in 2029 (Effigy 6). Between 2019 and 2029, net Medicare spending is also projected to grow every bit a share of the federal budget—from fourteen.3 percent to 18.3 percent—and the nation'southward economy—from 3.0 percent to 4.1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Effigy 6: Bodily and Projected Internet Medicare Spending, 2010-2029

Spending Growth Rate Projections for the Next 10 Years

- Average almanac growth in total Medicare spending is projected to be college between 2018 and 2028 than between 2010 and 2018 (7.9 pct versus four.four percent) (Figure 4).

- On a per capita ground, Medicare spending is besides projected to abound at a faster rate between 2018 and 2028 (five.1 pct) than betwixt 2010 and 2018 (1.seven percent), and slightly faster than the boilerplate annual growth in per capita private health insurance spending over the next 10 years (4.6 percent).

- Medicare'south actuaries projection a higher per capita growth rate in the coming decade for each part of Medicare, compared to their 2010-2018 growth rates: 6.0 percent for Function B, 4.4 pct for Part D, and 4.3 pct for Role A (Effigy 5).

- Among the reasons cited for projected growth in Part B spending are legislative changes in the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2018, including repeal of the Independent Payment Advisory Lath (which as well affects Part A and Part D spending projections) and repealing annual limits on therapy services covered under Role B, and college Medicare Reward spending. Projected increases in Part B per capita spending will pb to increases in the Role B premium and deductible.

- The projected increase in Part D per capita spending growth is driven by a slowdown in the generic dispensing rate and increased specialty drug utilize, offset past higher manufacturer rebates negotiated past private plans and a decline in spending for hepatitis C drugs, which was a meaning commuter of higher full Role D spending in 2014 and 2015.

Long-term Spending Projections

Over the longer term (that is, beyond the next 10 years), both CBO and OACT expect Medicare spending to ascent more than chop-chop than Gdp due to a number of factors, including the aging of the population and faster growth in wellness care costs than growth in the economy on a per capita footing. According to CBO'southward almost recent long-term projections, net Medicare spending will grow from 3.0 per centum of Gdp in 2019 to 6.0 percent in 2049.

Over the adjacent 30 years, CBO projects that "excess" health care cost growth—defined every bit the extent to which the growth of wellness intendance costs per beneficiary, adjusted for demographic changes, exceeds the per person growth of potential GDP (the maximum sustainable output of the economic system)—will account for half of the increase in spending on the nation's major health care programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and subsidies for ACA Market place coverage), and the crumbling of the population will business relationship for the other one-half.

How is Medicare Financed?

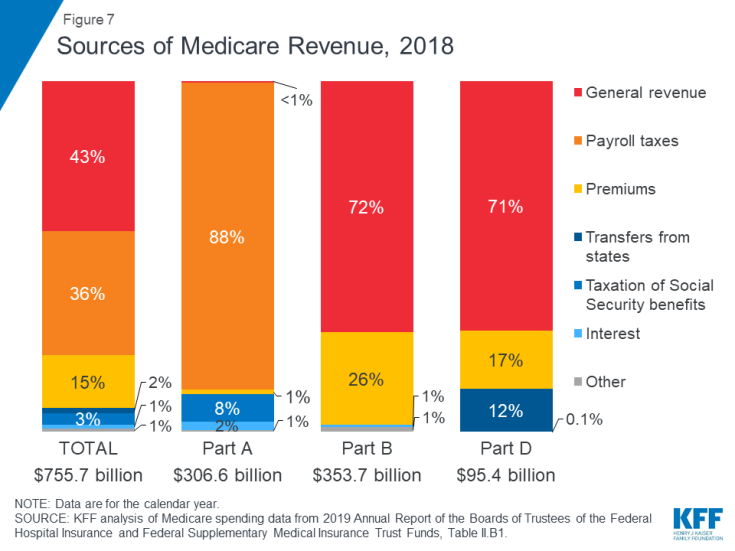

Medicare is funded primarily from general revenues (43 percent), payroll taxes (36 percent), and casher premiums (xv percent) (Figure 7).

Figure seven: Sources of Medicare Revenue, 2018

- Part A is financed primarily through a ii.ix percent revenue enhancement on earnings paid by employers and employees (1.45 percent each) (accounting for 88 pct of Part A revenue). Higher-income taxpayers (more than than $200,000/individual and $250,000/couple) pay a higher payroll tax on earnings (2.35 percentage).

- Role B is financed through general revenues (72 percent), casher premiums (26 percent), and involvement and other sources (2 percent). Beneficiaries with annual incomes over $85,000/individual or $170,000/couple pay a higher, income-related Role B premium reflecting a larger share of total Office B spending, ranging from 35 percent to 85 percent.

- Role D is financed by full general revenues (71 percentage), beneficiary premiums (17 percent), and state payments for beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (12 percentage). Higher-income enrollees pay a larger share of the toll of Part D coverage, as they do for Part B.

- The Medicare Reward programme (Part C) is not separately financed. Medicare Advantage plans, such as HMOs and PPOs, cover Part A, Part B, and (typically) Part D benefits. Beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans pay the Part B premium, and may pay an additional premium if required by their programme; nigh half of Medicare Advantage enrollees pay no additional premium.

Assessing Medicare's Fiscal Status

Medicare's fiscal condition can be assessed in different ways, including comparing various measures of Medicare spending—overall or per capita—to other spending measures, such every bit Medicare spending as a share of the federal budget or as a share of Gdp, equally discussed above, and estimating the solvency of the Medicare Hospital Insurance (Office A) trust fund.

Solvency of the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund

The solvency of the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund, out of which Office A benefits are paid, is one way of measuring Medicare's financial status, though because it only focuses on the status of Office A, it does non present a complete picture of total program spending. The solvency of Medicare in this context is measured by the level of assets in the Office A trust fund. In years when annual income to the trust fund exceeds benefits spending, the asset level increases, and when annual spending exceeds income, the asset level decreases. When spending exceeds income and the avails are fully depleted, Medicare volition not have sufficient funds to pay all Part A benefits.

Each year, Medicare's actuaries provide an estimate of the year when the nugget level is projected to be fully depleted. In the 2019 Medicare Trustees written report, the actuaries projected that the Function A trust fund will be depleted in 2026, the same year as their 2018 projection and three years earlier than their 2017 projection (Figure 8). The actuaries gauge that Medicare will exist able to cover 89 percent of Part A costs from payroll taxation revenue in 2026.

Figure 8: Figure 8: Solvency Projections of the Medicare Role A Trust Fund, 2005-2019

In the 2018 and 2019 Medicare Trustees reports, the actuaries attributed the earlier depletion date to several factors, including legislative changes enacted since the 2017 report that will reduce revenues to the Part A trust fund and increase Part A spending:

- lower-than-expected revenues from payroll taxes in 2017 and 2018 due to lowered wages and lower levels of projected Gdp;

- lower revenue projections from taxation of Social Security benefits (which provided 8 percent of Part A revenues in 2018) as a issue of the tax cut legislation enacted in December 2017;

- higher-than-expected spending for Part A benefits and higher projected provider payment updates;

- college spending projections due repeal of the ACA'south individual mandate, which is expected to increase the number of people without wellness insurance, which will result in an increment in Medicare'southward disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments for uninsured patients; and

- college spending projections due to repeal of the Contained Payment Informational Board, which would have helped to control Medicare spending if the growth charge per unit exceeded certain target levels.

In full general, Part A trust fund solvency is also affected by the level of growth in the economic system, which affects Medicare's acquirement from payroll taxation contributions, by overall health intendance spending trends, and past demographic trends—of note, an increasing number of beneficiaries, specially between 2010 and 2030 when the baby blast generation reaches Medicare eligibility historic period, and a declining ratio of workers per beneficiary making payroll taxation contributions.

Part B and Part D do not accept financing challenges similar to Part A, because both are funded by beneficiary premiums and general revenues that are ready annually to lucifer expected outlays. Expected future increases in spending nether Office B and Part D, however, will require increases in full general revenue funding and higher premiums paid by beneficiaries.

The Future Outlook

Although Medicare spending is on a slower up trajectory now than in past decades, total and per capita annual growth rates are trending college than their historically low levels of the by few years. The aging of the population, growth in Medicare enrollment due to the baby boom generation reaching the age of eligibility, and increases in per capita health care costs are leading to growth in overall Medicare spending. At the same fourth dimension, recent legislative changes, including repeal of the ACA's individual mandate and repealing IPAB, have worsened the short-term outlook for the Medicare Part A trust fund and have led to projections of college Medicare spending in the hereafter.

A number of changes to Medicare accept been proposed in the past to address the fiscal challenges posed by the aging of the population and rising health care costs. Lately, policymakers accept been focused more narrowly on policy options to control Medicare prescription drug spending, rather than on broader proposals to reduce the growth in Medicare spending. And there has been piddling discussion of revenue options that could be considered to aid finance intendance for Medicare's growing and aging population, including raising the Medicare payroll tax or increasing other existing taxes. Meanwhile, Medicare has featured prominently in the 2020 presidential campaign, with proposals from some Democratic candidates to expand on it as office of a Medicare-for-all programme, and ideas from others to allow people to buy into information technology.

The prospects for proposals that would impact Medicare's financial outlook are unknown, only they volition require conscientious deliberation over the effects on not just the program's finances only also its growing number of beneficiaries.

Source: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/the-facts-on-medicare-spending-and-financing/

Posted by: levinethaverce.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Does Medicare Collect Each Year"

Post a Comment